by David Balashinsky

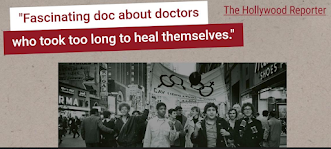

In "Every Body," directed by Julie Cohen, the plight of intersex people and the growing success of the intersex rights movement are at last receiving the attention they deserve. It might not be an exaggeration to say that the intersex rights movement has arrived. In the last several years, two large hospitals have announced that they will no longer perform certain types of medically unnecessary intersex surgeries. One of them has even taken the unusual step of apologizing for having performed these surgeries in the past. The intersex rights movement also recently has begun to achieve success legislatively. For example, in 2021, Austin's city council passed a resolution condemning "nonconsensual and medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children." A half dozen mostly European nations have gone further, banning (most of) these surgeries, outright. Now, with "Every Body" playing in theaters across the nation, Cohen is helping to raise the public's awareness of this issue. These developments - in medical practice, legislatively and socially - are all hallmarks of an idea whose time has come. For all these reasons and more, "Every Body" is a hugely important film and I urge everyone - every body - to go see (or stream) it.

I

have only one criticism of "Every Body" and, while it is only one, this

criticism ties in to what I believe to be a serious and ongoing problem

within both human rights discourse and the genital autonomy movement broadly. Because this one flaw in

Cohen's film epitomizes this problem, and without intending to detract in

any way from this beautifully-made and inspiring documentary itself, I believe

that the time is right - and that it's not unreasonable - to call attention to it.

The case that prompted Cohen to make her film in the first place is the tragic story of David Reimer. Reimer was one of a set of identical twin boys who were both, at the age of seven months, diagnosed with phimosis. It's important to understand here that, generally throughout childhood, the penile prepuce (the foreskin) remains fused to the glans, a normal condition that is known as physiological phimosis. In infancy, true, pathological phimosis is extremely rare. However, partly because of their unfamiliarity with intact penises, physicians frequently mistake physiological phimosis for pathological phimosis. Consequently, in infancy, "phimosis" is almost always a misdiagnosis of what is, in fact, the natural state of the child's penis. There is every reason to think then, that the diagnosis of phimosis that both boys received was a case of a physician pathologizing a normal physiological condition. Not surprisingly, the boys' pediatrician recommended the treatment of choice which, at the time, was circumcision. This was subsequently carried out by Jean-Marie Huot, a general practitioner, who opted to use, instead of a scalpel, an electrosurgical device (a Bovie cautery machine, to be precise). In the process, David's entire penis was obliterated - literally burnt to a crisp. Distraught, his parents turned to one of the world's most prominent sex- and gender researchers, John Money, who had been promoting his theory that gender is "malleable" for the first couple years of a child's life. Money recommended that David be raised as a girl and that his parents do everything in their power to reinforce their son's gender as female. The unique circumstances of David's having been born male but raised female while his identical twin brother was raised male made the twins ideal as living experiment-and-control subjects. Thus, above and beyond providing a solution to the predicament the family (especially David) was faced with, the experiment would also serve to confirm Money's theory - if it worked. It didn't. Thanks to the courageous and diligent efforts of Doctors Milton Diamond and H. Keith Sigmundson, Money's claims, far from being confirmed, were debunked. As for David, he never felt right living as a girl, he ultimately rejected the gender that had been imposed on him and he lived a short, troubled life that he ended himself with a shotgun blast at the age of 38.

It's also important to keep in mind here that, like physiological phimosis, ambiguous or indeterminate genitals - "intersex" - occur naturally and, in most cases, do not pose a problem for the individual who is born intersex. Consequently, the surgical modification of the genitals of intersex children that became standard protocol during the 1970s is, like the treatment of physiological phimosis, simply a case of physicians having pathologized and then "treating" what is in fact a natural and benign condition.

The David Reimer case is not merely relevant to the practice of intersex surgery but foundational to it. Before being discredited and even since, Reimer's putative "successful" transition from male to female through surgery, hormonal treatments and social conditioning was cited as proof of the efficacy of surgical sex- and gender-assignment and used, therefore, to justify the subsequent genital- and body-modifications to which who-knows-how-many intersex children were subjected. A considerable portion of "Every Body," therefore, is appropriately devoted to the David Reimer case.

But before there was intersex surgery there was penile circumcision. And before David Reimer's sex, gender and identity were tampered with, his penis was. It bears repeating here that the botched circumcision in this case was prompted, in all likelihood, not by a pathological condition but by a physician's having pathologized a normal one. The problem, then, was not that Reimer's attempted circumcision was botched but that it was attempted in the first place. The circumcision itself that was imposed on David Reimer, therefore, was the prime mover: the first in a concatenation of events that led, through diverging paths, to the disastrous outcomes in David's own life, to numerous unwanted and unnecessary intersex surgeries on other children, to the rise of the intersex rights movement, even to the making of Cohen's film. I take it as axiomatic that, when connecting dots, the first dot is the most important and yet it is this dot that Cohen fails to connect to all the others. It's not that Cohen fails to mention Reimer's circumcision - it would be impossible not to. But Cohen seems to regard the original attempted surgical modification of David's penis as incidental: relevant to her subject only because its untoward and catastrophic results led to his being raised as a girl and because his allegedly successful sexual reassignment was then used to justify subsequent intersex surgeries on other children. Thus, Cohen treats David's circumcision as something that stands apart, conceptually, from the equally unnecessary intersex surgeries that her film documents (and implicitly condemns). As a result, this can leave the viewer with the impression that the problems that David faced in his life and that so many other intersex people would face in theirs did not begin at the moment the decision was made to subject David to circumcision but only after the decision had been made to subject him to sex- and gender-reassignment. That is the one conceptual flaw in Cohen's film.

I want to be clear that I fully respect the right of a filmmaker to focus

on whatever topic she chooses and, in presenting that topic to her

viewers, to circumscribe her camera's field of view as narrowly as she

deems appropriate. Viewed strictly as a documentary about intersex people,

intersex surgery and the intersex rights movement, it might seem unfair to criticize "Every Body" for not going far enough and to criticize Cohen for not connecting all the dots.

But "Every Body" is about much more than chromosomes and gonads. To view it superficially, as though that were all there is to it, would be to miss its larger point. The deeper message of "Every Body" - its fundamental truth - is that every body has an inherent right to exist as nature made them. This is the guiding principle against which every norm, every injustice and every harm documented in the film stands in opposition, from what was done to David Reimer, to the imposition on intersex children of a socially-constructed and strict binary view of human sexuality (two absolute and mutually exclusive sexes, with nothing in between), to the imposition on transgender individuals of a parallel and equally rigid view of gender, to "bathroom bills" - and, especially - to physicians surgically "fixing" bodies that they themselves have needlessly pathologized. More than anything, then, "Every Body" is an unequivocal condemnation of the practice of pathologizing naturally-occurring but harmless anatomical features - especially genitals - of human bodies and surgically altering them without consent in order to make them conform to socially-constructed standards of appropriateness or normalcy. Nota bene: that is not just a description of intersex surgery - it is the very essence of routine penile circumcision. That is why Cohen's failure at least to acknowledge as much in her film is disappointing.

Again, I'm not faulting Cohen for failing to make a movie about circumcision. There are already several important films - "Whose Body, Whose Rights?", "Cut - Slicing Through the Myths of Circumcision" and "American Circumcision" - that have attempted to do for people with penises what Cohen has now attempted to do for people with intersex traits. But it's impossible to view intersex surgery accurately, both in theory and in practice, without contextualizing it within medicine's long history of pathologizing natural and harmless conditions (homosexuality and the penile prepuce are prime examples) and within its long-established practice of using these contrived pathologies as a justification for administering treatments that are neither needed nor desired and, especially, as a justification for performing medically unnecessary surgeries on the genitals of unconsenting children. By the time surgical modification of the genitals of intersex children became standard protocol, medical professionals in the United States already had been performing surgical modifications to the normal genitals of infant males for decades. In fact, at that point, most fully and normally developed infant penises were being operated on. With a precedent like that, what chance might the anomalous genitals of the 0.5 to 1.7 percent of the population that is intersex stand?

Viewed this way, David Reimer's circumcision is neither extraneous nor even incidental to the story that, in "Every Body," Cohen seeks to tell. That fact that his circumcision, in all probability, and like the vast majority of the million-plus infant circumcisions that are still performed every year in the United States, occurred for no other reason than that Reimer's penis had been patholgized, and because the surgery was therefore both medically unnecessary and imposed on Reimer without his consent makes it, in every way that matters, not just similar in its particulars but morally indistinguishable from the intersex surgeries that are the main focus of Cohen's film.

It is not only in large ways - that is, in principle - but in small ones, too, that nontherapeutic penile circumcision is identical to at least a major portion of intersex surgeries. I do not know what the statistics are - intersex surgeries run the gamut from clitoral reduction to the removal of internal testes - but these would be those surgeries that are intended to "normalize" the external genitalia of intersex children in order to make them appear more stereotypically "male" or "female." As a report by Human Rights Watch explains,

"Intersex," sometimes called "Disorders or Differences of Sex Development (DSD) in medical literature and by practitioners, encompasses around 30 different health conditions that affect chromosomes, gonads, and internal and external genitalia. In many cases, a significant factor motivating surgical intervention - and often the primary rationale for it [my emphasis] - is the fact that these conditions cause children's genitalia to differ from what is socially expected of men's [again, my emphasis] and women's bodies.

Similarly and in parallel, social acceptability and meeting cultural expectations about the appearance of a child's genitals are also often the primary rationales for surgically altering a child's penis from an intact one to a circumcised one ("so he won't be made fun of in the locker room," "so his future sex partners won't be turned off"). By the same token, conformity with culturally-determined anatomical standards is embodied in that other stand-by justification for nontherapeutic penile circumcision: "so he will look like his father."

The more sinister aspect of cultural expectations, of course, is the body shaming by which they are enforced. Alicia Roth Weigel, one of the intersex activists profiled in "Every Body," makes this point:

We are told by doctors from the moment that we are born that our bodies are shameful and that they are a problem and need to be fixed and oftentimes we undergo nonconsensual surgeries. . . . We all have different physical traits or . . . sex traits that maybe some people aren't accustomed to but we are fighting for the message that diversity is a beautiful thing. . . .

What I would tell Weigel, if I had the opportunity, is that there are millions of people with penises in this country who can relate, to one degree or another, with this statement. The harsh truth is that it is not only intersex people - those with visibly atypical genitalia - whose genitals have been pathologized by the medical establishment. The medicalization and normalization of penile circumcision have created a culture in which the penile prepuce has been utterly stigmatized. Body-shaming of people with intact penises continues to be rampant and socially acceptable. As a result, every person with a penis - whether circumcised or intact - grows up with the perception that they were born with a congenital "deformity" of their penis that either was "corrected" through circumcision or, if it wasn't, ought to have been. And every time a physician performs a medically unnecessary circumcision, that physician contributes to this body-shaming culture. Yet another similarity between intersex surgeries and penile circumcision is that both have been and continue to be rationalized on the basis of their putative benefits and prophylactic value. But, in both cases, the evidence to support these claims is scant and, even when present, the anticipated health benefits - which may not be realized for years or even decades to come, if ever - do not justify depriving people of their right to make such personal medical decisions for themselves. This is a point that is argued forcefully by Weigel. In an interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air (NPR), Weigel explains how the internal testes with which she was born came to be surgically removed when she was less than one year old:

Doctors . . . told my parents that I had internal testes . . . and that my internal testes could become cancerous one day and so they recommended removing them as soon as possible. And here's the kicker: anyone who is born with testes could get cancer one day; that is true. What we now know . . . is my risk of getting cancer is only somewhere between one and five percent and much later in life; that cancer never happens in childhood for people born like me, or very rarely if it ever does. And so because of a somewhere between one and five percent risk of cancer they decided to remove my hormone-producing organs without asking me. . . . Essentially, by trying to fix something that wasn't even broken, they created problems. . . . By trying to fix me, they broke me.

This is how many circumcision survivors feel. (I'm sure it's how David Reimer felt, too.) And, by way of comparison, the risks of developing any of the diseases its boosters claim that neonatal circumcision can help prevent are also comparably low. As Frisch et al. point out,

. . . [about] 1% of boys will develop a UTI [urinary tract infection] within the first years of life. There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) linking UTIs to circumcision status. The evidence for clinically significant protection is weak, and with easy access to health care, deaths or long-term negative medical consequences of UTIs are rare. [Morever,] UTI incidence does not seem to be lower in the United States, with high circumcision rates compared with Europe with low circumcision rates. . . . Using reasonable estimates . . . for every 100 circumcisions, one case of UTI may be prevented [but] at the cost of two cases of hemorrhage, infection or, in rare instances, more severe outcomes or even death.

So with penile cancer ("one of the rarest forms of cancer in the Western world"), STIs, HIV & AIDS:

. . . only one of the . . . arguments has some theoretical relevance in relation to infant male circumcision; namely, the questionable argument of UTI prevention in infant boys. The other claimed health benefits are also questionable, weak, and likely to have little public health relevance in a Western context, and they do not represent compelling reasons for surgery before boys are old enough to decide for themselves. . . .

The importance of allowing individuals to exercise informed consent - to decide for themselves which parts of their bodies they are permitted to keep - that Frisch et al. are asserting here with respect to penile circumcision is mirrored exactly in the sentiments expressed by intersex rights activists. Here's Weigel, again:

[A]n analogous example I like to give . . . [is] the BRCA gene. . . . The BRCA gene is a genetic variant that confers with it a high risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer and the risk of cancer if someone is born with the BRCA gene is much, much, much, much, much higher than my one-to-five-percent risk of testicular cancer ever would have been. But you don't see them force-removing little girls' ovaries who are born with the BRCA gene because they could get cancer one day. They wait until the girl is a certain age where she is able to make an informed decision with her consent. . . .

We

have suffered these nonconsensual and medically-unnecessary surgeries

that everyone from the United Nations to the World Health Organization

condemn as torture - they call it genital mutilation - and entire

countries have banned these practices. . . . Unfortunately, they happen

every day in accredited hospitals in the United States.

I do not know how often an intersex child is subjected to a medically unnecessary surgery in the United States but even once per day is once per day too often. At the same time, it's worth remembering that medically unnecessary penile circumcisions occur more than three thousand times every day in accredited hospitals in the United States.

If one accepts the premise of "Every Body" that intersex surgery is a medically unnecessary, nonconsensual body modification that is unethical in and of itself because it violates a person's rights to bodily integrity and self determination, it is difficult to see how can one look at the practice of nontherapeutic penile circumcision (let alone at what happened to David Reimer) and not come to the same conclusion about it, not form the same moral judgement about it, and not be as outraged by it.

My own view is that, as an abstract principle, any medically unnecessary surgery (that is, a surgery not urgently necessary to save life or limb) that is imposed on someone without that person's consent is unethical.

Keeping that principle in mind, it doesn't matter what the surgery is and it doesn't matter what the sex or the gender of the victim is.

Keeping all of this in mind, all of the particulars of David Reimer's case - not just some of them - matter and are therefore inseparable from the premise of "Every Body." A more appropriate way to have presented David Reimer, then, would be not merely as an unfortunate victim of happenstance or of medical incompetence who subsequently became a victim of medical malpractice but, rather, as the man whose very life (and, likely, death) represents the nexus between medically unnecessary penile circumcision and medically unnecessary intersex surgery.

For this very reason, the most appropriate way to honor David Reimer's memory is to take from his case the lesson that the campaigns to end all medically unnecessary, nonconsensual genital (and other, non-genital) surgeries are, fundamentally, one and the same. It is high time that the movements to end nontherapeutic penile circumcision, medically unnecessary intersex surgeries and female genital cutting (FGC) made common cause with one another and formed the strategic alliances that moral consistency and common sense demand. The failure of these three pillars of the genital autonomy movement to unite on the basis of their shared logical, philosophical and ethical foundations is the ongoing problem within the genital autonomy movement, and within human rights discourse, more broadly, of which "Every Body" is, I began by observing, a good, if unwitting, illustration.

I am not suggesting that it is somehow wrong for intersex rights activists to focus primarily on banning medically unnecessary intersex surgeries, for anti-FGC activists to focus primarily on banning FGC, or for anti-MGC (male genital cutting) activists to focus primarily on banning MGC, just as I am not suggesting that it was wrong for Cohen to make the intersex rights movement the primary focus of her film. But I do think that it would be beneficial to all of these groups to present a united front to the world and to support one another by at least acknowledging their shared values and objectives and by treating one another as respected and valued allies. Similarly, organizations concerned with promoting human rights more generally and with promoting the common good should be morally consistent and adopt a position of inclusion when condemning harmful practices that violate the rights of children. Too often, however, the opposite has been the case.

Sometimes this is a failure of omission but sometimes, one of commission. Equality Now, for example, used to have a "fact sheet" (and I use the quotation marks advisedly) on female genital mutilation (FGM) in which the author or authors went out of their way to differentiate FGM from nontherapeutic penile circumcision, representing the former as abhorrent and never justifiable and the latter as benign. This fact sheet included the eye-popping statement that "circumcision is the removal of foreskin and does not affect the male sex organ itself." (The male foreskin, or prepuce, is, of course, an integral part of the penis - as integral to the penis, in fact, as any part of the external genitalia, including the female foreskin, is to the vulva.) In contrast, the statement continued, "FGM damages the sex organs, inhibiting pleasure and causing severe pain and complications for women's sexual and reproductive health." It's a small but encouraging sign that Equality Now has since scrubbed from its site language denying the critical erogenous function of the penile foreskin and dismissing the human rights violation that necessarily occurs when it is surgically removed without consent.

But Equality Now is not the only organization that has gone out of its way to distinguish female genital cutting from male genital cutting. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS have gone even further, explicitly promoting male genital cutting while, at the same time, condemning female genital cutting.

The reluctance by these organizations and others within the anti-FGC movement to recognize the similarities between FGC and MGC is hard to fathom. Likewise, their apparent aversion to accepting the banning of nontherapeutic penile circumcision as a valid human rights concern. Both campaigns to end genital cutting (that is, of penises and vulvas), like the intersex rights movement, rest on the same ethical and philosophical foundation: the right of every individual to bodily self-ownership - the right to control one's own body. Yet, paradoxically, there appears to be a notion among some within the anti-FGC movement that the movement risks becoming trivialized or diluted by making common cause with the anti-MGC movement. The thinking seems to be that, because FGC is so much worse, MGC can't be all that bad. Or perhaps there is an apprehension by some that the true horrors of FGC can only adequately be characterized by distinguishing it from MGC. But, even allowing that, in certain cases (but by no means all) FGC is more harmful than MGC, that is like reasoning that it's okay to cut off a boy's hand simply because cutting off a girl's arm is so much worse. Both are wrong and it is morally inconsistent and ultimately counterproductive for opponents of FGC to view opponents of MGC as competitors in a zero-sum game.

An example of the failure of some to acknowledge others within the genital autonomy movement through an act of omission (although someone who is pessimistic about human nature might also view this as an act of commission) would be the post by Organisation Intersex International Europe last year in which it made a point of linking FGM and IGM (intersex genital mutilation) conceptually and strategically while conspicuously omitting male genital mutilation (MGM). The meme, which was posted on Twitter, depicts a flower suspended between two hands, each coming from opposite ends of the image. Next to one hand is the caption "#EndFGM" and, next to the other, the caption "#StopIGM."

Other notable examples can be found outside the genital autonomy movement. The WHO, the United Nations and several other important human-rights- and physicians' organizations, including Physicians for Human Rights, the American Academy of Family Physicians, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, "have condemned medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex youth" while remaining silent on equally unnecessary genital surgeries on children with penises.

Still another example of this failure has been the subject of much of this essay: Julie Cohen's film, "Every Body," in which the original pathologizing and medical mismanagement of David Reimer's genitals are passed over and implicitly treated as being fundamentally distinct from the pathologizing and medical mismanagement of the genitals of intersex people.

In contrast to these exclusionary approaches to genital autonomy is the work of bioethicist Brian D. Earp and others who argue for a unified, ethical approach to solving the problem of genital cutting in all its various forms. On the question, "Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and male circumcision: Should there be a separate ethical discourse?," Earp concludes,

It is . . . to be welcomed that ethicists, activists and other stakeholders have been campaigning to protect the rights of girls to be free from non-therapeutic, nonconsensual cutting into their genital organs. I cannot state enough that I am in support of such efforts. . . . My argument has been that they should not be stopping there. Female, male and intersex genital cutting . . . should be done exclusively with a medical indication or with the informed consent of the individual. Children of whatever gender should not have healthy parts of their most intimate sexual organs removed before such a time as they can understand what is at stake in such a surgery and agree to it themselves.

A model of promoting unity and emphasizing the shared objectives of the three branches of the genital autonomy movement is the Worldwide Day of Genital Autonomy (WWDOGA). Although WWDOGA commemorates a judicial ruling vindicating the rights of a victim of male, or penile, genital cutting, the creators and organizers of this annual event have taken pains to deliver a message of universality on behalf of all victims and potential victims of genital cutting. WWDOGA calls for "protection for all children from non-therapeutic genital interventions" and "Genital self-determination regardless of sex traits, gender, religion, tradition or where you come from." Additionally, WWDOGA endorses The 2012 Helsinki Declaration of the Right to Genital Autonomy which states, in part,

Whereas it is the fundamental and inherent right of each human being to security without regard to age, sex, gender, ethnicity or religion as articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child[,]

Now we declare the existence of a fundamental right of each human being a Right of Genital Autonomy, that is the right to:

* personal control of their own genital and reproductive organs; and

* protection from medically unnecessary genital modification and other irreversible reproductive interventions.

Another modest but nonetheless important example of inclusiveness and support for its sibling movements by an organization created primarily to eradicate nontherapeutic, nonconsensual penile circumcision can be found in the Values Statement of the Genital Autonomy Legal Defense and Education Fund (GALDEF) which begins with these words:

GALDEF promotes solidarity with female and intersex victims of genital cutting and we recognize that some transgender people have also been harmed by penile circumcision.

(Full disclosure: I serve on the board of directors of GALDEF.) Most recently, GALDEF has issued a public statement in support of the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation.

There are several reasons why the three pillars of the genital autonomy movement should view and honor one another as allies, and these include not just philosophical reasons but strategic and practical ones as well. Above all, it's the right thing to do.

A good illustration - and a good example of making common cause - is, again, provided by Alicia Weigel, herself. (If I have given an unfair amount of space here to Weigel, it's because she is featured prominently in "Every Body" and is a prominent spokesperson for the intersex rights movement. Additionally, it is because her comments, not surprisingly, are so relevant to the cause of banning nontherapeutic penile circumcision. Beyond all this, she also happens to be tremendously quotable.) Weigel, who also serves as a Human Rights Commissioner for the City of Austin, was asked by Terry Gross (in the Fresh Air interview, linked above) what she thought are the strengths and potential drawbacks of intersex people being included with the other communities represented respectively by the initials "LGBTQIA," with the "I," of course, standing for "intersex." As Weigel explained,

We share so many common experiences. Just like people who grow up gay, grow up often feeling ashamed simply for existing, or might have undergone conversion therapy whereas intersex kids also undergo conversion therapy just using surgeons and scalpels, instead of electric shocks. We also hold a lot in common with the trans community in that we often have had surgeries that change our bodies' gender presentation. . . . So there's so much natural overlap and allyship between our experience that I think it makes total sense to include us in that community. Just like there are some gay people who are closeted and not out, there are some intersex people who I think also don't consider themselves part of the LGBTQI+ community - and maybe it's because they're straight in terms of their sexuality; or the choice of their gender was not wrong. But, for me, including us as part of that community helps all the other letters of the acronym feel compelled to stand up for us; just like the gay community was so vital in the trans folks finally getting a platform to stand up for their needs, we are now asking on all of our brothers, sisters and comrades in the broader queer and trans community to now fight for us, too. Because, just like I showed up to help kill the bathroom bill, even though it wouldn't necessarily have affected me - it already says "female" on my birth certificate and I pee in the women's room - I was there to really help my trans friends that day, we really hope our gay and queer and trans friends will stick up for us as well, understanding that all of our liberation is intricately bound up in one another's progress [my emphasis].

The intersectionality expressed in this statement can, of course, be expanded even further. There are literally millions of people with penises who have the exact same anger and resentment about what was done to their bodies that intersex people have about what was done to theirs. I

hope, for this reason, that Weigel may come to look upon these people with these

bodies too as her natural allies and that they, in turn, will view and support Cohen's film and embrace

Weigel, the other courageous stars of "Every Body," Sean Saifa Wall and

River Gallo, and the entire intersex rights movement as allies.

Another prominent intersex rights advocate, and one who has publicly made the connection between the movements to ban all forms of genital cutting (and other forms of medically unnecessary intersex surgeries), is Mx. Anunnaki Ray Marquez. Marquez (who is also tremendously quotable: my favorite is "When you've met one intersex person, you've met one intersex person.") is the first person in the state of Colorado to receive (retroactively, and after fifteen months of fighting for it) an intersex birth certificate. Marquez truly embodies the spirit of intersectionality and of making common cause with all movements to ban genital cutting.

Ultimately, the right to bodily integrity and the right to genital autonomy rest on the foundation of bodily self-ownership, no matter whose body we're talking about. Either there is a fundamental right to bodily self-ownership that applies to every body, regardless of sex, or there isn't. And, if there is, that means that that right is not just fundamental but universal.

This ties in to the underlying concept of Cohen's film just as it does to Weigel's comments about inclusion. Importantly, the demands for justice and equality by any one group within the abbreviation "LGBTQIA" are not trivialized or diminished by the inclusion of any other group within that assemblage. The cause of advancing gay rights, for example, is not undermined by linking it conceptually and strategically to the cause of advancing intersex rights. By the same token, the

right of intersex people and people with vulvas to autonomous control over their bodies (especially their genitals and reproductive organs) is not diminished, trivialized or threatened by acknowledging that that same right belongs no less to people who happen to have been born with

penises. On the contrary: that right can only be strengthened by recognizing its universality. It's self-evident that a morally consistent

principle is more powerful than one with a carve-out that omits 50% of

the population. Hence, the

campaigns to end female genital cutting and medically-unnecessary intersex surgeries can

only be strengthened by joining forces with the campaign to end male genital cutting. Establishing the right to be free

from nonconsensual genital surgery on the foundation of a universal right of bodily self-ownership rather than on a right narrowly tailored to protect only people with vulvas or only people with intersex traits will help secure and guarantee this right for Every Body.

* * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * *

* *

About me: I am originally from New York City and now live near the

Finger Lakes region of New York. I am a licensed physical therapist and I write about bodily autonomy and

human rights, gender, culture, and politics. I currently serve on the board of directors for the Genital Autonomy Legal Defense & Education Fund, (GALDEF), the board of

directors and advisors for Doctors Opposing Circumcision and the leadership team for Bruchim.