by David Balashinsky

In the history of the gay rights movement, certain events stand out as milestones. First and foremost is the Stonewall uprising in 1969. Another is the termination by Congress of the Defense Department's "Don't Ask - Don't Tell" policy in 2010 allowing lesbian, gay and bisexual people to serve openly in the armed forces. Still another is the Supreme Court's 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges recognizing the right to same-sex marriage.

Less

well known by the general public is

the decision in 1973 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to drop its classification of homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder.

Although it's hard to believe now that gay women and men were once

subjected to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT, or "shock therapy") and

other "treatments," for decades the APA viewed homosexuality as a

condition that needed to be "cured." Women and men were not merely

stigmatized for being gay; their homosexuality was actually defined as a pathological condition by the

medical establishment. As a result, among other interventions that would now be condemned as medical

malpractice, gay people were institutionalized, subjected to"aversive

therapy" (a technique that involved, in the case of gay men, exposing

them to pictures of nude or semi-nude men while administering electric shocks) and even

subjected to lobotomies - all in an effort to "cure" them of their gayness.

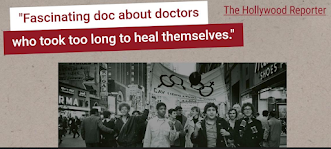

It took years of advocacy and even direct confrontation before the APA was finally persuaded by gay rights activists (from within but mostly outside the organization) to revise its official stance on homosexuality. The story of how these activists overcame decades of entrenched thinking within the APA is movingly told in the powerful, heartbreaking yet inspiring documentary, "Cured."

Anyone who cares about human rights should watch this film. Anyone who cars about the rights of LGBTQIA+ persons should watch this film. And anyone who cares about ending all forms of forced genital cutting should watch this film. Why? Partly because the gay rights movement has been phenomenally successful and there is always something to learn from a successful human rights movement. But, more particularly, because the battles for gay rights that have been fought over the past 60 years and more have been waged within the social sphere, within the legal domain and within the realm of medical practice. It is precisely in this respect that the gay rights- and genital autonomy movements have so much in common.

It goes without saying that both movements represent quests for fundamental human rights. What right is more fundamental, after all, than the right not to have healthy, erogenous tissue surgically removed from one's body without consent? At the same time, there are other rights perhaps not as crucial as the inviolability of one's physical boundaries but that are still important enough to be regarded as fundamental. Chief among these is the right to equal protection. The aim of the gay rights movement is for gay people to have the same rights to housing, employment, marriage, services and public accommodations, government benefits, healthcare and the myriad other rights that (some - not all) hetero people take for granted (rights that, at least, exist on paper). These particular rights are typically legal rights: that is, they are either codified in statutes or they are rooted even more deeply in the texts of constitutions. Additionally, an important aim of the gay rights movement has been and continues to be for social acceptance: not just of homosexual relationships but of homosexuality itself, as something intrinsic to an individual's identity. Gay people want what all of us want: the right to live openly as themselves and without apology for who they are. A third domain in which gay people have had to fight for their fundamental rights is the subject of "Cured": their treatment (in both senses of the word) by the medical profession. All of these specific rights can be distilled down to fundamental human rights but it is significant that the struggle to achieve them has taken place within each of these three domains: the law, society, and medical practice.

This is exactly the case with the movement to end nontherapeutic penile circumcision (male genital cutting, or MGC), which comprises one of the three major pillars of the genital autonomy movement (the other two being the FGM-eradication movement and the movement to end the medically unnecessary surgeries that are imposed on intersex children in a misguided attempt to "normalize" their bodies). Just as the gay rights movement has done, the MGC-eradication movement is pursuing its aims within each of these three spheres. For example, the groundwork is now being laid for the pursuit of creative and effective legal strategies to redress individual cases of harm while creating impact litigation that will have a positive deterrent effect more broadly on the practice of subjecting unconsenting minors to medically unnecessary, irreversible and life-altering genital surgery. That is the focus and raison d'être of the Genital Autonomy Legal Defence and Education Fund (GALDEF). At the same time, campaigns within the social sphere to normalize intactness and to destigmatize the penile prepuce are gaining momentum. Within the medical sphere, more and more physicians, physicians' organizations and other healthcare providers and medical ethicists are publicly stating their opposition to the practice of MGC.

Notwithstanding these encouraging developments, the penile prepuce continues to be disparaged and worse by the medical profession. It is particularly within the realm of medical practice, therefore, that the penile prepuce bears such a striking similarity to the state of being gay. Both the penile prepuce and homosexuality have an overlapping history of explicit pathologizing by the medical establishment. Both have been regarded, therefore, by medical professionals as conditions that warranted aggressive interventions for the well-being of the "patient." In both cases, the goal of these interventions was the same: the elimination of the offending pathological condition.

It's worth bearing in mind that none of the three domains discussed here - law, society and medical practice - is entirely walled off (or "siloed") from the other two. There is an active interplay between all of them as the prevailing normative values of each influence and, in turn, are influenced by the others. That is partly why the problem of MGC has proved so intractable. The unwarranted privilege it has enjoyed within the legal realm is unquestionably due to its persistent social acceptability and the gloss of legitimacy that it continues to receive from the medical profession. By the same token, the medical profession continues to cite societal acceptance of MGC (including parental preference and prerogative) as justifications for its continued availability (and for third-party payment for it). And the fact that legal sanctions have yet to be imposed upon any physician for performing what is nevertheless universally understood to be a medically unnecessary surgery - in contrast to other cases in which physicians have been prosecuted for and even convicted of performing medically unnecessary surgeries - surely indirectly reinforces the continued acceptance within the societal and medical realms for MGC. By failing to prosecute medical professionals and others for performing any medically unnecessary penile circumcision - an act that, were it to involve any other body part, would be considered not just malpractice but battery - the state implicitly bestows its imprimatur on MGC and does so explicitly in those states (and there are still 34 of them) in which Medicaid Funds are used to pay for it.

But if each one of these three domains supports the other two and, together, all of them undergird the practice of nontherapeutic penile circumcision, it is also true that, like a three-legged stool, without any one of them, the stool must inevitably fall down. Therein lies cause for hope. That is why it is imperative that the struggle to eradicate MGC be waged in the legal sphere (in courts and in legislatures), in the public sphere (through media and online forums, through one-on-one engagement and through public protest) and in the medical sphere (through outreach to medical school faculties and students and to medical professionals, through efforts to defund nontherapeutic circumcision by eliminating third-party payments for it, such as Medicaid, through education aimed at new parents and through vociferous advocacy with medical organizations and regulatory bodies).

Fortunately, not only has exactly this sort of three-pronged approach been employed before but it has succeeded. To see how, we need only look to the gay rights movement. In particular, the medical prong - the campaign by gay rights activists targeting the APA's pathologizing of homosexuality - is a paradigm of effective grassroots advocacy. That is the story told by "Cured," which is why this documentary is must-see viewing for those who support the cause of genital autonomy.

This post was originally published as a promotion for a fundraising event to benefit GALDEF that took place on 17 September 2023 which included a special screening of "Cured." It has now been revised, accordingly. You can learn about distribution efforts for "Cured" by following it on Facebook, Instagram and X. If you're interested in contacting the flimmakers, they can be reached at "Cured"'s website. The producers of "Cured" have also created a Resource List. Finally, if you would like to learn more about GALDEF or donate, please visit our website.

* * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * *

* *